-

Missouri Just Reformed Its Sex-Offender Registry. But 1,200 Offenders Are Missing

Until very recently, Missouri’s sex-offender registry functioned like a factory with a single product. Regardless of the crime they’d committed, the state treated everyone on it like a potential predator, placing thousands of people on a single lifetime registry with strict 90-day check-ins, residency restrictions and virtually no chance of removal.

That system changed in August, when Governor Mike Parson signed into law a bill mandating a new multi-tiered system that can distinguish between, for example, a violent sexual assault and possession of child pornography, or statutory rape and public urination. That system brings Missouri into line with dozens of other states.

But the long tenure of Missouri’s one-size-fits-all registry has left a legacy of problems.

Missouri’s sex offender registry was created in 1995, and it now contains more than 15,000 names. While the state allows certain offenders to petition for release, only 175 people have successfully been removed since 2007. By comparison, Kansas reportedly removes that number of offenders from its registry every single year.

And the sheer size of Missouri’s registry seems to have overwhelmed the system. According to an audit released yesterday, the state cannot account for 1,259 sex offenders. Almost 800 of those are classified as Tier 3 offenders under the new law — a designation reserved for the most severe sex crimes.

The audit places the blame firmly on the shoulders of local law enforcement agencies, which are supposed to keep track of all offenders in their jurisdiction and ensure that they’re checking in regularly.

But across Missouri, that’s not happening. In a press conference yesterday, Missouri Auditor Nicole Galloway noted that the publicly accessible database of sex offenders — a system managed by the Missouri State Highway Patrol — contains numerous inaccuracies, at times incorrectly labeling offenders compliant when they are not.

“This is alarming,” Galloway said, adding that she hopes the report will spur quick action by local police agencies. “Without accountability public safety can be compromised,” she said.

Failures uncovered by the audit span both bad police work and clumsy data entry. Of the nearly 1,300 non-compliant offenders, only 239 are listed as absconders in local police databases. The remainder, the audit charges, have been left alone in violation of state law, unchecked and unrestricted.

According to the audit, 1,020 non-compliant offenders averaged more than three years since their last registration; twenty percent haven’t registered in more than five. Yet the audit found that warrants have not been issued for 91 percent of non-compliant offenders.

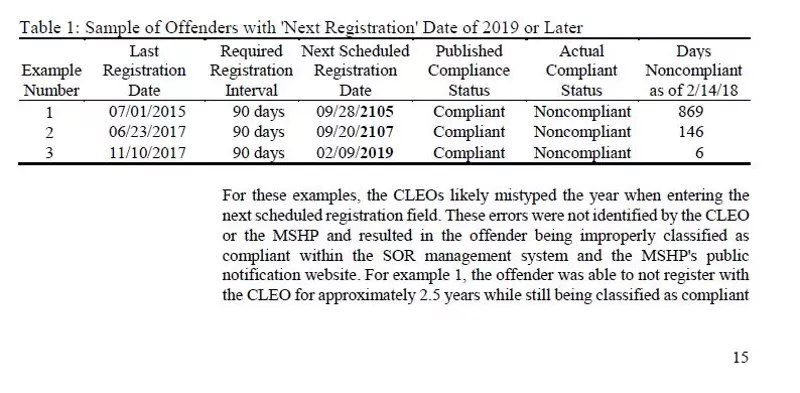

And even when local police are checking on their jurisdiction’s offenders, the data is sometimes entered wrong. The audit includes examples of police officials mistyping an offender’s next registration date, in one case entering 2105 instead of 2015. In that instance, the system labeled the offender as compliant, even though, to date, he or she hasn’t registered in 869 days.

- Via Missouri Auditor

- The audit report included examples of data-entry errors, fooling the database into labeling non-compliant offenders as compliant.

During the press conference, Galloway acknowledged that Missouri police departments have long struggled to enforce the rules of the registry.

“I’m hoping that by bringing attention to this issue, local officials will be compelled to act quickly,” she said.

The burden of sex offender enforcement appears have hit St. Louis city particularly hard. The audit found that of the city’s 1,265 registered sex offenders, 244 are non-compliant, a rate of 19.3 percent. That leaves St. Louis city with the second highest percentage of non-compliant offenders in Missouri, trailing only Jackson County.

Law enforcement failures, Galloway noted, create ripple effects. If a local police department doesn’t apply for warrants or fails to identify non-compliant offenders, there’s no way for another agency to pick up the slack. If an officer pulls over a non-compliant offender for a traffic violation, he won’t know to take action.

Beyond that, public trust and safety is at stake.

“Things are falling through the cracks and the laws are not being enforced,” Galloway said. “The sex offender registry is providing a false sense of security.”

On that latter point, Vicki Henry would agree. As president of Women Against Registry, or WAR, Henry advocates for families with those on the registry. She testified before the legislature in favor of the bill that instituted separate tiers to Missouri’s sex offender laws.

But she’d like to go further. Henry believes the public sex offender registry — the database allows anyone to see offenders’ mugshots and addresses, not just law enforcement — should be abolished.

“We’re creating a moral panic,” Henry warns.

She says that Galloway’s audit reinforces the faulty assumption that harsh restrictions are the only thing keeping the offenders from recommitting heinous crimes. In reality, though, the subject of sex offender recidivism is contentious, and even U.S. Supreme Court decisions on the matter have been called into question for relying on shoddy (or nonexistent) evidence.

Henry wasn’t surprised to learn the audit’s results. Sex offenders routinely lose jobs or residences, and there’s always a danger that a neighbor (or vigilante) will find their names and photos on the public registry. Additionally, homelessness is rampant among sex offenders, making the listed addresses in the public registry suspect at best.

Henry’s own organization once used the addresses listed on the Missouri Highway Patrol database to send mailers to individual offenders. “We had mail come back,” she says. “They can’t keep the data straight, they don’t have the manpower for all of that.”

In a way, Henry does agree with Galloway that the weakest link in the state registry system is local police agencies. But she worries that these local departments — which are already struggling to accomplish basic data entry — aren’t ready to handle the new tasks needed to accomplish the legislature’s reforms.

For example, the new law requires the Highway Patrol update its public registry to show an individual offender’s tier. Henry says she’s already received multiple reports that the tiers are being incorrectly entered, and that even low-level offenders are being labeled as tier 3.

“Not only do we have a real screwed up system,” Henry insists, “we are putting families in danger by having a public registry.”

Henry, the subject of a 2017 RFT cover story, argues that tough-on-crime stances like Galloway’s might play well at press conferences, but they ignore the reality for the offenders’ families, who ultimately share the impact of lifetime registration requirements.

Henry knows the impact of Missouri’s registry first-hand. Her own son, who spoke to RFT on condition of anonymity for our 2017 cover story, spent 48 months in a Navy prison and treatment center for possessing child pornography. He then lived with his mother for the next six years, but in September 2017, he was arrested in a SWAT raid at Henry’s home. He’s now facing two separate federal charges, one for possessing child pornography, and the second for unlawful possession of a firearm — a charge connected to an attempted suicide.

The issues at play are painful and complicated, and Henry acknowledges that the registry was created with good intentions. Still, she’d rather see the registry’s information restricted to law enforcement.

But it’s those very police departments that are continuing to lose offenders, even as Missouri’s auditor is publicly blasting them to do more.

“I’m concerned,” Henry says, “that we’re creating more of a quagmire.”

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at Danny.Wicentowski@RiverfrontTimes.comRedemption or forever condemned? Nevada to embark on new sex offender registry system, but critics say it’s overly harsh

Missouri Just Reformed Its Sex-Offender Registry. But 1,200 Offenders Are Missing

Arizona MVD a Bit Unusual

Make sure you know current requirements. You can go to your Sheriff's Office website to see if there is new information there. If so, we suggest you do a screen print and save it. Call your registry office to get clarification on any questions you might have. Document the date, time, who you spoke with and their instructions regarding any address change, vehicle, employment, travel dates if required, etc.

Keep in mind if you are required to update your drivers license annually through the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) you should contact them for their status.

Be safe, be smart, stay healthy and know we will get through this.Stay Updated with Arizona W.A.R.

All information is confidential and we do not distribute any data whatsoever.

The W.A.R. Support Line:

Links to and From WAR

WAR